The Essential "Art" – Drawing. Thoughts on projects and designs by Franco Pierluisi. Alessandro Anselmi

If to design means to "think while drawing", then Franco Pierluisi was one of its main figures and advocate.

Thought and drawing, thought and construction of form in art are indissociable and, together with the connection of language and thought in literature, it is one of the main points of modern culture, and we could even say is a larger degree of freedom compared to historic legacies.

Rigor in thought and freedom in figurative arts, then.

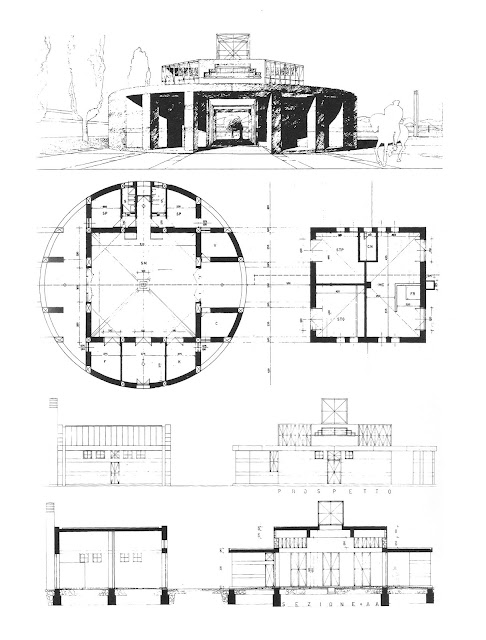

Of this rigor and this freedom is what Franco lived, expressing his graphical talent at every level of the complex hierarchy of architectural creativity. His floor plans, for example, are always a methodological model where rationality, typological and figurative both, turns into the exactitude of the geometry but without compositional rigidness, geometry is reinforced in his rigor by apparent "tremblings" in the gesture. Here is the dialogue between the construction of the space (the abstraction) and its realization through the drawing (its determination in the unique, irreplaceable and unrepeatable poetic "of the hand").

Towards the end of the Sixties, the project that G.R.A.U presented in the competition for the new Camera dei Deputati in Rome was titled "Determined Abstraction", almost making of this method a manifesto. Franco didn't participate directly but this motto and his way of thinking would have existed at all if it wasn't for the essential contribution of Pierluisi in another project, another competition, for the monument for the Quattro Giornate di Napoli.

I think that those wonderful drawings testify the dialogue between an expressive and gesturally determined reality and the will of a geometric abstraction in the construction of the space. But there is more, even before Robert Venturi experiences, when the graphics of a phrase, from the work of Eduardo De Filippo and suggested by himself, became the protagonist of the project and then reinforced the indissociability of language and thought, even in their multiplicity.

"A da passà a nuttata" ["He has to survive the night"] became, in a period dominated by sociological culture and urbanist theories, the reaffirmation of autonomous valors of architecture.

Nowadays, "the night passed" and having registered the successes of architecture (at least in Europe and in the western world, except in Italy, of course) we are again conscious of the limits of the irreplaceable presence of this activity (of this discipline?) in the construction of "landmarks" of collective desires. Franco was always aware of this, so much to make the research of symbolical meanings one of the center of his expression. Here comes his interest in the human figure, not much as a symbol of centrality, but more as an iconography capable of measuring an "historical measure", capable of revealing with strength and clarity the "antecedent" and the distance of meanings from that figure and the reality of drawings and projects. It is not by chance that Franco never drew the human figure directly but always through symbols, figures dense with meanings and truth, able to give to the latter new meanings.

In all of this you can feel the flow of energy that some years ago we would have called the flow of history. But even now we have to ask ourselves, while contemplating Franco's drawings: what is the meaning for artists and architects of facing toward future (and this is inevitable, since the design activity makes sense only in the future tense) without facing the past, too? In a period when oblivion feeds and reassures neo-romantic feelings of new avant-garde, we feel it's again necessary to affirm that the vital flow exists only because of this paradox. The Architect as an Artist is always Janus the two-faced.

But architecture, history, the simulacrum are not enough in defining the complex figurative problematic in the drawings by Franco. For example, in a lot of them, the herm and architecture are born from the very same earth, almost signifying an obscure origin of all things. The veiled mystery under stratifications are unveiled in drawings of underground caves, where figurative events live as in the mother's womb; above them, the territory of light gathers strength in this darkness, showing how art is born from the most apparent "disequilibrium".

Light and darkness: it's in this dialogue that Franco's drawings are born. Light-Darkness is what animate all of his projects, and in the section they found the most elevate and adequate expressive meaning. But "sections" are his elevations, too, so full of matter and shadow, so connected to Mother Earth that they appear as her transformation; a great demonstration of his quality in architecture! In this Franco Pierluisi was absolutely "roman" in the most elevate meaning. Son of Sangallo, Peruzzi, Vignola, dramatically complex as Borromini, elegant as Bernini, interested in nature as Valadier, to name some of the ancient masters, but he was a pupil of De Renzi and Ridolfi too, Franco sketched by instinct thick walls, plastic masses, clever projections that under the mediterranean light define, always, the image of Roman architecture.

Elevations conceived as sections, plans conceived as sections, blackened by shadows, lead immediately to the places of history, where Time has done his mutilations (his own "sections") and where empty windows and missing roofs reveal – finally! – the hidden logic, intimate secrets of architectural beauty. The truth, finally, without lies of the "function", where to find inspirations and where Franco Pierluisi found the validity of many of his projects.

The places of history, the archeological areas, contain, then, the truth of architecture and must be considered the "primal places" of the struggle to the form: this is what Franco's drawings show to us and this is what archeologists will never understand. What is the point of speaking of archeology, of "primal places", of "object without memory", without their context and without figuring out their return to Nature? Another lesson of truth from which we can understand that the "meaning" of architecture cannot be separated from his original, "natural place" even if it is an urban context. On the other hand what would be the meaning of the architectural order, if not to evoke the vivifying contradiction between logical geometry and nature's randomness? From this point of view, every problem in architecture is always a "landscape" problem, in the single building as in the city, if we intend as "landscape" the grafting of randomness to the rigor of reason (this is, to those who can see, the real lesson of archeology and its sites). But the archetype of a landscape is Rome!; and this category wouldn't have a meaning if the river's handle, the sacred willow, the walls and the pomer, the abstract pyramid, the anachronistic cylinder and the giant Bramante's recess over there wouldn't have been formalized in four hundred years of artistic production (for example let's consider Cavalier Pussino, so foreigner that he became one of the lesser sons of the city, but also Duilio Cambellotti and Aristide Sartorio, whose images, immersed in malaria, remember us that such a heroic and lyric landscape has been also an image of endless pain, for a millennia), that Franco always referenced.

There's no concession to longing over that "old unit" in Franco, too analytical and rigorous his method, born out of rationalist thinking in that autodidact school that we traversed together in the second half of the fifties, too confident and cultivated his graphical sign, mindful of the Picasso's lesson and of echoes of Informal.

Franco had studied the high schools proficiently, always getting high marks, he knew greek and latin, but also mathematics, geometry and of course history of art. He learnt drawing by himself with deep eye and profound intelligence, he loved drawings, he loved thinking through drawing, we already said that; and that's why we don't find any formalism, no self-indulgence in his works.

To conclude and to get back to initial consideration of the inflation of figurative expression in our times, a note, an apparently ironic one: Pierluisi was one of the first to use the computer, and he was a master of the "Hand". A pity, his death has deprived us of the first and original virtual images (and those were truly able of overcoming that figurative magma we discussed at the beginning of these notes!) but also of new paths to take and authentic, deep feelings.

original text by Alessandro Anselmi inAdueARCHITETTURA Periodico del LId’A_Laboratorio Internazionale d’Architettura RC, edited by Centro Stampa, Ateneo – Reggio Calabria, December 2009.

original text by Alessandro Anselmi inAdueARCHITETTURA Periodico del LId’A_Laboratorio Internazionale d’Architettura RC, edited by Centro Stampa, Ateneo – Reggio Calabria, December 2009.