Paolo Portoghesi - I GRANDI ARCHITETTI DEL NOVECENTO, Edited by Newton Compton - 1998

G.R.A.U.

Several years ago, when I tried to make a point about their work, the GRAU was mostly a «spiritual» reality. Many architects gazed the sky: Isti mirant stella was the motto for one of their best works and it would also become the title of a book. Slowly but surely, after some interesting designs, the first few built works started to arrive: not quite symphonic compositions, more like chamber music, but their vocation toward orchestral pieces was strongly present, well expressed after all in those bigger contemporary works.

In the next fifteen years, more important works were designed and some more distinct personalities started to emerge under the common signature. The discrimination and persecution of all the members also started to gradually vanish, a discrimination that kept them away from universities and mostly limited to marginal roles. Numerous international prizes and the attention gained by some reviews allowed their work to be recognised and appreciated around the world. Works finally built contributed to free them from the shadow of minor representatives of “local chamber music”.

But this recognition as rightful members of the history of architecture was never accompanied — we have to say — by a correct assessment on their importance as the most specific and intense voice of Roman culture in the recent years. Someone could say that this specific Roman quality is their weakest point (almost a form of refined provincialism) in their historic role; but it is, again, an unacceptable discrimination.

Toward the end of the XIX century the American historian H. Adams wrote about Rome and said: «Irresistibly seducing and […] the worst place in the world to teach a young man of the XIX century what to do in the XX century». Anyone who thinks this idea to be true and thought about criticising GRAU about their brave “regionality" is missing an important point: if Adams was right and even prophetical, his evaluation lost any reason since when the idea of a Modernity based on a complete amnesia about the past tradition has got a serious hit, losing its eschatological quality.

The “romanity” of GRAU is, in truth, their strong point in the will of rebuilding a connection between past and present and it has its paradigm in the layered and contradictory fabric of the city and in the “logic” of ruins, where architecture, deconstructing itself, is retold and disclosed.

Future historians will have to consider how Rome was a key reference for Kahn and Venturi both, for the GRAU, for Charles Moore, for Ungers, for Isozaki. And while for Le Corbusier Rome was the symbol of spatial unity in the architectural organism, for many architects of the later generations it has become — as a city more than a historic idea — the place of productive contradictions, creative inserts, interrupted and torn continuity, retrieved by matching different, incongruous fragments.

If the latest tendencies in architecture needed Rome again, beginning from the Quattrocento in European culture (a need that’s now represented by the monumental figure of the polish pope John Paul II), that need wasn’t traditional and conventional, celebrated in Grand Tours, it was the necessity of deeper certainties, to dig with doubt and detachment both. GRAU has had the great merit of focusing a condition of the design process akin to the archaeology, where myths are reborn and perish before our own eyes, leaving us full of knowledge and emptied by nostalgia.

«Reflecting now on our prior works» wrote Anselmi in 1985, «I noticed that I was never able to design a single, unitarian building; I usually designed a small group of elements, joint and assembled together. I feel that I always designed archaeological areas. I was always fascinated by ancient ruins and spatial situations born in archaeological areas. At the heart of cities and however so far from urban life, archaeological places force a new relationship with nature, and, in the end, with history itself. If history is a reformulation and a precise reconstruction of scientific ideas, ancient ruins are always there to destroy and contest those ideas. In a sense, it defines the limit of cognitive possibilities and at the same time, it transports to another dimension of time where every hierarchy is annihilated and past and future are one».

The condition of archaeology inspires Anna Di Noto too: starting from the description of a landscape, in Alba Fucens (near L’Aquila, Abruzzo), she gets to a design methodology. «The secret charm of the place», she writes, «(and of any other place long inhabited by men) is from the presence of many heterogeneous elements; the ordered city in form of a ruin, the randomly arranged modern houses, the involuntary acropolis, the free column and the wall that includes her to give rhythm to the sameness, the object inside the object, the reinvention of architecture built with ruins of what was there before the destruction brought by time and earthquakes.

A frequent aura in Italy that clever travellers have always noticed with a careful eye. “Being still or walking by, landscape of various kind appears: palaces and ruins, gardens and underbrushes, vast horizons and narrow bottlenecks, small houses, stables, triumphal arches and columns, often so amassed together that you can almost draw them in a single sheet of paper”. In Voyage in Italy, this is what Goethe wrote about Rome, about a city grown on herself as an infinite variations of a theme.

While designing, I always try to recount in a small time the same long voyage, I compose and aggregate fragments of known architecture in a sameness that excludes the chronological and typological inventory; making order I examine reactions produced by interferences towards the transformation in a new image of what I knew and experimented. Visual memory is the guide of the design process».

According to Pier Luigi Eroli, who keeps working with profound passion at the boundaries of painting and architecture, reaching results of great fascination, the archaeological image of a “petrified desert” is recalled in a poetic declaration, shaped into form in a poem dedicated to architecture:

For her i’m drowning

in immense deepness

Of dilated Void

inextricable blockage emerges

from remote Life.

And when sight dims

and the Place is empty

the soul falls

into a petrified desert.

The relationship with Rome as a palimpsest, as a continuous contamination of high and low levels, of order and chaos, ancient and modern, emerges also in the ostensibly sceptical position of Massimo Martini, who with his Architetture di strada offered an intense and oneiric re-reading of the city, deconstructing it in parts with interchangeable degrees. «I worked for years and years», Martini writes, «pushed by a moral reason (since I was horrified by the idea of “being versed”): a young man had to change the world of the fathers; a Marxist, if possible, had to do even more. The cultural life of GRAU, rightfully enclosed and aristocratic, softened every possible vulgarity of avant-garde, in a muffled climate of cloister-like quality. Everything flowed and found reason in a pure struggle of ideas (in the context of the stubborn concept of designing beautifully even an elevator shaft); everything looked as having sense beyond simply elaborated forms; almost independent from them, even though we defined ourselves “marxists” and “formalists”; our moral position and the “group” guaranteed some kind of messianic quality to our every act.

Then they came to us telling that we had won the rightful prize we reserved for ourselves, the prize of having confessed it: a prize for eternity; a place, a quote in the coveted History of Art. It would have been vulgar, for people like us, to keep persisting in how and how many times we confessed that. The time of history restored its flow, and the enchantment vanished away.

Today I work only for those elaborated forms and the curiosity, anxiety, insatiability, that defined, and continue to define, my drawings. I still don’t feel versed in something. It’s the very effect of my work that keeps me. As Wim Wenders says, “A story exist only within a story”».

Giuseppe Milani wrote about the poetry of ruins: «Among the working material that I use more often there’s the image of ruins. In the evolution of this figure I can now recognise some phases. At the beginning I was simply fascinated by the relationship between ruin and place, how the ruin can absorb nature in its surroundings, in large scale complexes such as Palatino or Santuario Prenestino in Rome. In that phase (1965, with R. Mariotti) the public housing in Marino was born. A wall eroded and segmented where the obsessive geometric determination was asked to calm down into its surroundings. To put it like Simmel would, “an ascending strength of the spirit” (what we called logical reason, or “aggregative law”) against the “descending strength of Nature”».

Form eroded by life leads back to living forms: «After that, I asked [the image of ruins] to collaborate since the beginning of the design process: in the same way salt defined the intimate form of an eroded trunk on the seashore, freeing the deeper, hardened fibres.

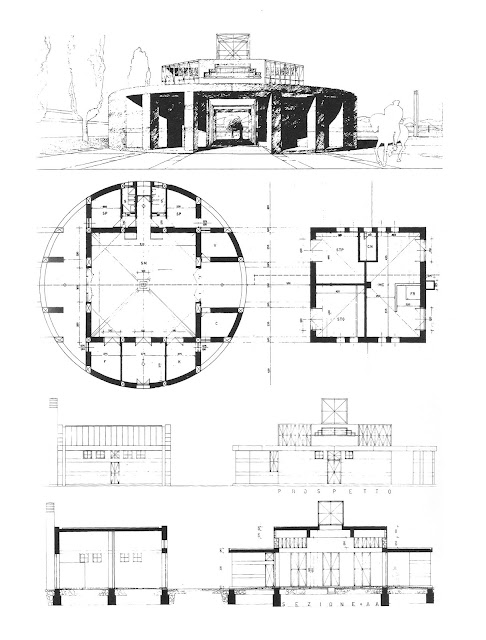

Brick ruins in the roman countryside, like the vaulted hall of Villa Gordiani, are the new references. At the same time, here begins the meditation upon ruins as a place where time and weather have produced a variety of rhetorical figures: projections, translations, sections, junctions of opposites and so on. In this phase, the small Villa in Palinuro (1969) is a significative example. In more recent time, all of this got reabsorbed and reversed in an image that wants to represent the coexistence of different times and layers, close to the idea of Freud in Civilization and Its Discontents, a vision of Rome synchronous with all its monuments. An example of this image could be the Republican Temple that still emerges in the walls of San Nicola’s Church in Foro Olitorio».

According to Francesco Montuori ruins are not simply an object, but a fertile idea. Living among ruins is a human condition, we all participate in it and, after all, a mass of ruins (maybe those that the Angelus Novus of Benjamin would leave behind), it’s the legacy of the Modern Movement.

«The great machine of progress looked capable of destroying every trace of past and of imposing its infinite power; history’s oblivion, market of antiquities, dominion over Nature, that was paradoxically wanted “on a human scale”, were its principles. On the opposite, the research of a relationship with nature and history is what guides anyone who wants to cross the landscape of ruins left by the Modern Movement. The allusion to ruins is not fortuitous: they are an architectural figure that testimonies the presence of a “will of creativity” from Nature herself, that ridicules every attempt to complete control: even the indestructible prisms of the World Trade Centre mirror themselves in ruins. But ruins are also the door that allow us to enter the world of images that we inherit from history; they are presented both as incarnate history and allegory of Time: it is the place of absence that spins back the wheel of time towards an index where nothing got lost, without any chronological order of events and meanings, where recent images live together with those of the past, in a choreography that only memory can figure out; it is the sign of preexistence as an instantaneous image of all the stages of history, final stage of the infinite transformations of Time and Nature, revelation of new and unexpected figures and relationships.»

This meditation on ruins according to Montuori gets translated into a fitting design for Piazza Vittorio in Rome, a symbiosis of coexistent signs. «We must listen to the voice of ruins; not only to get a simple reference but to cross, in both directions, the boundary between past and present: this is a dialectic and political act, it rouses the opaqued waters of a past, that hide not only memories but prophecies from the Book of Life».

By weaving together in a multicoloured fabric all the different intentions the architects of GRAU, as they expressed them around the half of the eighties, I don’t mean to crystallise a continuously evolving architectural thought, it’s more of an encouragement to notice again the “romanity” in their work and way of thinking: Rome as the city of ruins, but also of solid “classical” certainties, that make appear as ruins or fake ruins all those artificial constructions of ideologies, when they present themselves — and they often do! — as fake conscience.

In that sense Franco Pierluisi’s testimony is the most touching; not only because Franco is not with us anymore, but because for the city of Rome, this Rome-Palimpsest, master of productive contradiction and inserts, he gave a convincing definition of the christian-medieval hortus mirabilis, a city to “discover” and “continue”, «revealed by digging and freeing the hidden image, buried under layers of one hundred years of disorder and ignorance».

With his “franciscan” way of doing, impregnated with humility and sacred furor, Franco looked like he could have jumped out of a move like Francesco giullare di Dio, by Rossellini or Uccellacci e uccellini by Pasolini. His invectives and tender elegies dedicated to the architecture of the past sounded like calls from a lost paradise, where dwelt not only joy and holy innocence, but authentic human suffering. To Pierluisi Rome was a Mater Matuta, a morning-mother that every day rises again, waking up from slumber: «It’s incredible how no one understand that those few architects with enough ideas and strength must intervene swiftly, that they need a free hand, not only in designing, but also in guiding, restoring and protecting the monumental or symbolical fate of the Forma Urbis, recall it, free from the wounds that put at risk the transmission to future. It’s also incredible how one of the key-symbols of western civilisation, an essential legacy of the human spirituality has to perish, suffocated by ignorance, blandness and violence of this politics».

His reflections on Rome, city to be “continued”, instead of “expanded”, should become a central thought for anyone who’s to intervene in this city, because they correctly assess the multiple responsibilities that are bound to our generation, more than the others, for out legacy must not be tragically depleted. «Rome is its countryside, the view of Colli Albani far away and the Lepini hills, the view of the unforgettable Soratte (Vides ut alta stet nive candida […]), of the Circeo drowned in sunsets. Rome can’t be separated by the yellow walls of the Campidoglio, from the pines and dark cypresses of Gianicolo, moved by sea winds: the Countryside continuously emerges between the cables of urban fabrics and radiant urban systems, layered and expanded but not extraneous, from hanging gardens and villas behind tall walls manifests its continuous presence, it refuses to be built and destroyed anymore: thanks to this insuppressible prevalence of country, from the garden to the villa to the forest to the underbrush, the idea of hortus mirabilis embodies and determines itself, and it endures, even today».